5. Theory¶

Note

Only an overview of the theory is included here; details can be found in Ning [1].

The rotor aerodynamic analysis is based on blade element momentum (BEM) theory. Using BEM theory in a gradient-based rotor optimization problem can be challenging because of occasional convergence difficulties of the BEM equations. The standard approach to solving the BEM equations is to arrange the equations as functions of the axial and tangential induction factors and solve the fixed-point problem:

using either fixed-point iteration, Newton’s method, or a related fixed-point algorithm. An alternative approach is to use nonlinear optimization to minimize the sum of the squares of the residuals of the induction factors (or normal and tangential loads). Although these approaches are generally successful, they suffer from instabilities and failure to converge in some regions of the design space. Thus, they require increased complexity and/or heuristics (but may still not converge).

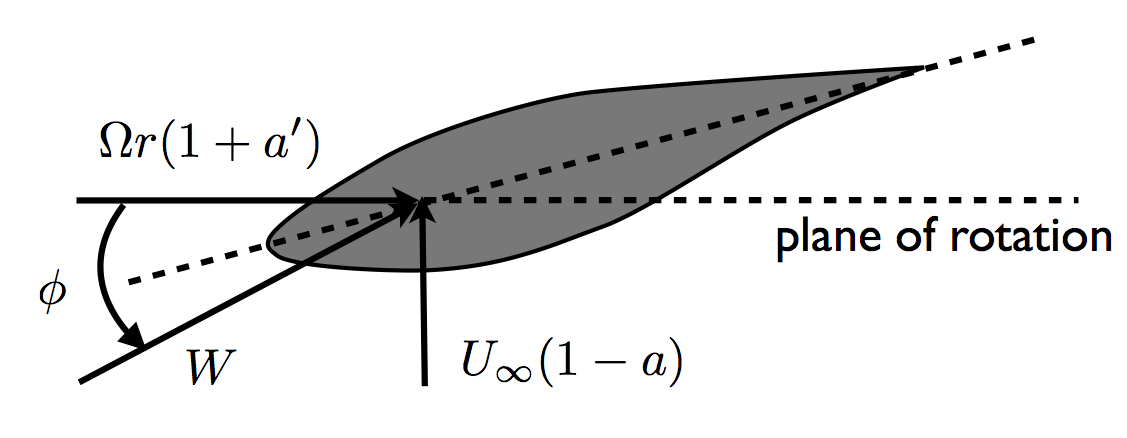

The new BEM methodology transforms the two-variable, fixed-point problem into an equivalent one-dimensional root-finding problem. This is enormously beneficial as methods exist for one-dimensional root-finding problems that are guaranteed to converge as long as an appropriate bracket can be found. The key insight to this reduction is to use the local inflow angle \(\phi\) and the magnitude of the inflow velocity \(W\) as the two unknowns in specifying the inflow conditions, rather than the traditional axial and tangential induction factors (see Figure 1).

This approach allows the BEM equations to be reduced to a one-dimensional residual function as a function of \(\phi\):

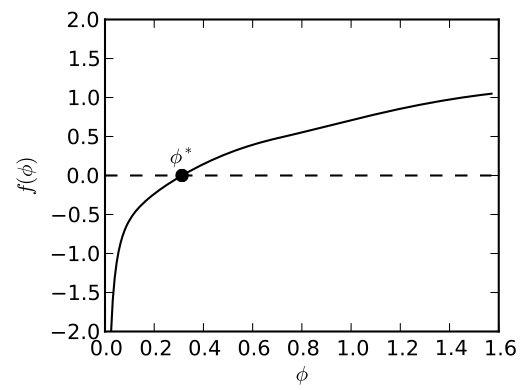

Figure 2 shows the typical behavior of \(R(\phi)\) over the range \(\phi \in (0, \pi/2]\). Almost all solutions for wind turbines fall within this range (for the provable convergence properties to be true, solutions outside of this range must also be considered). The referenced paper [1] demonstrates through mathematical proof that the methodology will always find a bracket to a zero of \(R(\phi)\) without any singularities in the interior. This proof, along with existing proofs for root-finding methods like Brent’s method [2], implies that a solution is guaranteed. Furthermore, not only is the solution guaranteed, but it can be found efficiently and in a continuous manner. This behavior allows the use of gradient-based algorithms to solve rotor optimization problems much more effectively than with traditional BEM solution approaches.

Figure 2: Residual function of BEM equations using new methodology. Solution point is where \(R(\phi) = 0\).

Any corrections to the BEM method can be used with this methodology (e.g., finite number of blades and skewed wake) as long as the axial induction factor can be expressed as a function of \(\phi\) (either explicitly or through a numerical solution). CCBlade chooses to include both hub and tip losses using Prandtl’s method [3] and a high-induction factor correction by Buhl [4]. Drag is included in the computation of the induction factors. However, all of these options can be toggled on or off.

Gradients are computed using a direct/adjoint (identical for one state variable) method. Let us define a functional (e.g., distributed load at one section), as:

Using the chain rule the total derivatives are given as

Bibliography

| [1] | (1, 2) S. Andrew Ning. A simple solution method for the blade element momentum equations with guaranteed convergence. Wind Energy, June 2013. doi:10.1002/we.1636. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/we.1636, doi:10.1002/we.1636. |

| [2] | Richard P. Brent. An algorithm with guaranteed convergence for finding a zero of a function. The Computer Journal, 14(4):422–425, 1971. doi:10.1093/comjnl/14.4.422. |

| [3] | H. Glauert. Airplane Propellers. Volume 4. Springer Verlag, 1935. |

| [4] | M. L. Buhl. A new empirical relationship between thrust coefficient and induction factor for the turbulent windmill state. NREL/TP-500-36834, National Renewable Energy Laboratory, Golden, CO, August 2005. |